The word for pebble in Hebrew is tz’zor. It is also the word for bond. In Jewish tradition it is customary to leave a pebble or stone atop a grave to show that you were there, that you remembered. The custom ties back to sitting shiva, the seven day mourning period associated with Jewish funerals. Like a stone, the mourner sits as friends and family visit, helping with the prayers, with the grief. Flowers die, dry and blow away, but stones are good at sitting.

More than anything, I needed to place stones on my ancestor’s graves. I needed our lost dead to know that they were found. They were purposefully forgotten, but here is my stone. You are known and will be remembered. I wanted my stones to hold them down in time like a paperweight so they wouldn’t blow away again. I also wanted the weight of my stones to pin Dorothy Sprague, my great-grandmother, to her lie. J’accuse! I wanted my stones to pile up like cairns, like markers to guide distant cousins to me. I’m here! I’m right here! Do you see me?

***

I don’t have an obsession with death per se, just my own death. To be more specific, I have an obsession with my funeral. Funerals are ceremonies wasted on the living. My fixation on planning my own end of times started well before my fixation on being Jewish, but both topics elicit heavy eyerolls from my friends and family.

“Look, all I’m saying is load my body into the back of your minivan, drive out to the wilderness, pop the back hatch, and hit the gas. My body’ll tumble out and Bob’s your uncle. Keep it simple. Feed a vulture.”

I had just outlined my current postmortem scheme to Mike and Lisa, my good friends and hosts in Teaneck, New Jersey, where I’d be staying for the New York City leg of my research trip. Mike and Lisa had invited another friend over for dinner and we were well into our first (or maybe third) cocktail. Okay, by we I mean me, but I was drinking rye whiskey, and this was research (more on that later). As I expected, the room went quiet. And then came the comments.

“Yeah, Porter…I’m pretty sure that’s not legal.”

“That’s not a funeral. That’s a body dump.”

“Yeah, I’m not doing that.”

There are so many ways to deal with the dead body of a loved one. You can embalm and entomb it, preserving the flesh and pomp for eternity (or close to it). You can stick it in a sack with some soil and the root ball of a sapling. You can burn it up until only ashes remain. This is one of the most common and prevailing methods of humans. Something about smoke rising up and dissipating into the ether, I suppose. And then you have cremains, a.k.a. the lumpy ashes and bone bits (nobody ever mentions the bone bits) to sprinkle off a cliff over-looking the ocean. Or you can compress them into a diamond and wear your gramma around your neck. Or shoot them out of a cannon a la Hunter S. Thompson. Or shoot them into space if you’re rich enough. You can mix them in clay and make a little pot. That’s what my mother did with her partner’s ashes. I want none of that. Roll me into the desert and let the scavengers have their fill. Farm to table.

***

When I was nine Uncle Dick, my mom’s brother died suddenly of a staff infection. He was only forty-one years old. He went into the dentist on Thursday with a high fever and was dead by Saturday. I remember my mom coming into my room when she found out he was in the hospital dying. I remember her waking me up crying and holding me and telling me that she needed to leave for a few days. I remember this was the first time I had really seen my mother weep, seen her knocked off her foundation, and I remember it frightened me a little bit. We all drove up to Maine for his memorial service. I remember adults milling around speaking in hushed tones. I remember muted colors and a blanket of gray clouds, but maybe that’s just me projecting “somber”. Most of all I remember two objects. One was Uncle Dick’s old Stetson, which I asked for and received. This hat would follow me through many adventures, but that’s the subject of another essay. The second object was a mix tape. Two actually. These two tapes, like the cowboy hat would play a fundamental role in who I was and how I thought about death.

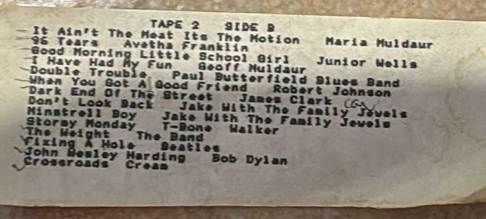

Dick was a audiophile. His record collection was a treasure, and when he died, my mom and his best friend went through his vinyl pulling choice tracks and recording them onto two cassette tapes.

*note: better scans to come

These songs and that hat would fuel a trajectory of folk music, guitar picking, and blues crooning that I am still on today, much to my teenage daughters’ dismay. “But let me tell you why this song was so important…”

I used to think that Dick’s music was him reaching back through time to shepherd me through my early teenhood, but really it was my Mom. Maybe she was making sure he wasn’t forgotten by inserting a little banjo and Delta blues into my formative years. Well, it worked. When I think of my own funeral, I think of a party. I think of music.

In addition to bearing the responsibility of actualizing my funeral ideas—one scheme involved an exploding casket that would shower raw meat upon the mourners (that was a hard no)—my poor wife has also been plagued with trying to remember all the songs I want played at my funeral. Eventually she forced me to just write them down. I was surprised that–considering my unhealthy preoccupation with my own death–that the Funeral Songs playlist in my Spotify account only has eight songs on it. And these eight songs aren’t all winners. Perhaps I forgot about the list when I came up with the body dump idea? Currently, my Funeral Songs playlist consists of the following tracks. I tried to arrange them in order starting with a few sad and pensive numbers:

Dress Sexy at my Funeral- Smog

Hard Drive- Evan Dando

My Blue Heaven- Gene Austin

And then come the pallbearers. Oh yeah, we’re in a church. I’m not very religious, but so what? Six handsome men in black suits come dancing out with my coffin to tune of:

Goin’ Down Slow- Bobby Blue Bland

This song is the piece de resistance. There is a version of this song on Dick’s medley by Geoff Mulduar titled I Have Had my Fun, which is essentially the same song, but there’s an incredible cathartic build in Bland’s version, and even though I’m pretty sure it’s about a guy dying of an STD, I still think it fits. Back to my funeral. The pallbearers have reached the alter (is that the correct direction for the body to travel?). We’re right at the end of the song, and there are horns and backup vocals and electric lead guitar and we’re building to a climax here, when suddenly my coffin blows open! And like Dracula rising from the dead, out pops a life-like mannequin of my body. BOOM! Jump scare! I look fabulous, of course. I’m dressed in a suit covered in silver sequins. Cue the next track:

96 Tears- ? and the Mysterions

Aretha Franklin’s version is on Tape 2 Side B, but I prefer the bouncy organ and wild 1960s garage band zeal of ? and the Mysterions. In the church, now the sounds of laughter overpower the weeping. Too many teardrops, baby. It’s time to boogie. The church turns into a dance party like that scene in Blues Brothers. Maybe my coffin is full of ice cold beer?

Fantastic Man- William Onyeabor

Because only a fantastic man would plan a party like this, right?

Pressure Drop- Toots & the Maytalls

Sweet relief.

Sweet Talkin’ Lady- Electric Light Orchestra

Yeah, I’m not sure how this got onto my funeral playlist, but it’s a damn good song, and I can’t seem to remove it. Don’t be hatin’ on ELO.

When I get into my funeral planning mode it can last awhile. I usually lose my friends and family in the process. My eyes get glassy. I get out of breath. My wife has to wait until I eventually lose steam and then, with a polite, but pointed “Remember, funerals are for the living,” she brings me back. And damn, she’s right. What I wouldn’t give to attend my own funeral.

***

I never wanted a gravestone. I never wanted to take up any additional space on this earth. I still don’t to some degree. But then I started visiting cemeteries. Troy Hill was my first on this trip. It was also the first journey among the steep slopes of Pittsburgh. Up, up, up. One-and-a-half lane streets, hairpin turns. I love the ever-present geography here, the ridges and rivers always asking something of its inhabitants, both uniting and dividing a population, allowing for each neighborhood to evolve its own endemic history, ethnicity and personality. Sara Petyk, my Pittsburgh host, told me she used to lead bike tours up to Troy Hill. My thighs bawk just thinking about the trek. Apparently, Troy Hill used to be a German neighborhood and just about every family would brew their own beer, growing their own hops, and storing their homebrew in the many caves that dimple the hillside. I wasn’t there to search for centuries-old pilsner. I was there to visit the grave of Bella Wormser, my fourth great grandmother, and to do that, I had to drive up to the top of Troy Hill to the first Jewish burial ground in Pittsburgh.

Two days prior, I spent a morning in the basement archive room of Rodef Shalom reading through the 1875-1906 meeting notes of Bes Almon Association, the oldest Jewish organization in Pittsburgh and a group in which my family were active members. More yellowed pages, more slanted ink, but also some insight into the work it takes to keep community and tradition alive in a rapidly changing United States. Much of the first few pages of the notebook were filled with notes on how to obtain land for a burial ground, which was important because there are many rules about how to deal with the dead. First and foremost, according to Halacha or Jewish law, the Jewish community must own the cemetery, and the deceased must own the plot. Deed in dead hand, and while that might be an exaggeration, it does create a memorable image. The members of Bes Almon had to purchase land, keep accurate records of who purchased which plot, and maintain the long and somewhat treacherous road up, up, up to the top of Troy Hill.

Second rule of a Jewish cemetery is that those buried in it must be Jewish. This seems obvious, I suppose, but it does get a little tricky when Jews start marrying gentiles and gentiles convert to Judaism. Could I be buried in a Jewish cemetery? I mean, since Judaism follows the maternal line, my mother is legally Jewish, and therefore I too am Jewish. “Ah,” say those that have noticed the tattoos adorning my skin. “You are far too inked to be buried with your Hebraic ancestors.” This is a myth. Traditionally, true. Nowadays, not so much. The idea goes back to keuod ha-met or “treating the dead and dead bodies with respect.” Cremations are still forbidden in Jewish burial practices and I imagine, so too is rolling a corpse out the back of a pick-up (back to the drawing board). Autopsies and organ donations, while traditionally forbidden, are now generally tolerated. Amputees are okay too, especially if you can bury the severed limb in a clearly delineated and properly deeded plot with a promise of reunion once you shuck your mortal coil.

The cemetery up on Troy Hill was small. About the amount of land you’d need for a couple of small houses with enough yard for a swing set and charcoal grill. My unit of measurement came easy as small houses and tards with swing sets and charcoal grills were what surrounded the graveyard, enveloped it. I parked as close to the remarkably unmarked gate as I could without blocking people into their driveway. Or maybe I was in a driveway? The single-story home directly abutting the cemetery was missing its aluminum siding exposing Tyvek like a freshly healed scrape. The site was on the side of a hill, not quite on the top, so I hefted my cameras and notebooks up to the top and began to methodically wind my way down, looking for Bella Wormser, Emmanuel’s mother.

A jay was screaming itself hoarse from somewhere inside a bent pine. It was cloudy and gray. Perfect graveyard weather. The headstones seemed ancient, many made of marble which had worn away to the point of erasure. Some had tipped forward and now lay face down in the earth with a still audible OOMPH! No identification there. I walked slowly, respectfully, reading the names like a mantra. But names are strange things. My reverence faded as I began to remember a highly inappropriate game my sister and I used to play with my stepmother. On long Saturday morning walks we’d have to pass through a cemetery, and we’d narrate the names to one another along with their causes of death. “Here lies Nimrod Salmon: Died of food poisoning (bad salmon).” “Here lies Moses Slammer. Died while serving time in prison.”

Bella’s grave was obvious and stood out with somewhat ostentatious pride. It was immense compared to every grave around it (how did I not notice it at once?). It was shaped like a bed, or maybe a lounge chair you might find by a pool but made of stone. It reminded me of the kind of grave from a Hammer film upon which you’d find a sexy vampiress sprawling seductively. It was the only one of its kind. Clearly the Werthheimer’s had money. Was that the message? I had forgotten a stone, so had to pinch a piece of gravel from the driveway near my car. Was this a fancy enough stone for Bella Wormser? It was rough, grayish green and slightly pyramidal. I rubbed at a smudge of asphalt on the corner. It would have to do.

When I returned to pick up my backpack where I had deposited it, I read a small plaque it’s edges softened by grass. It read: SOPHIA FLEISCHMAN, 1823-1848, PRESUMABLY, THE FIRST INTERMENT. Maybe the stones weren’t big enough.